More complex control cannot overcome Goodhart's Law: The Soviet experience

more metrics and more complex metrics don't solve the problem

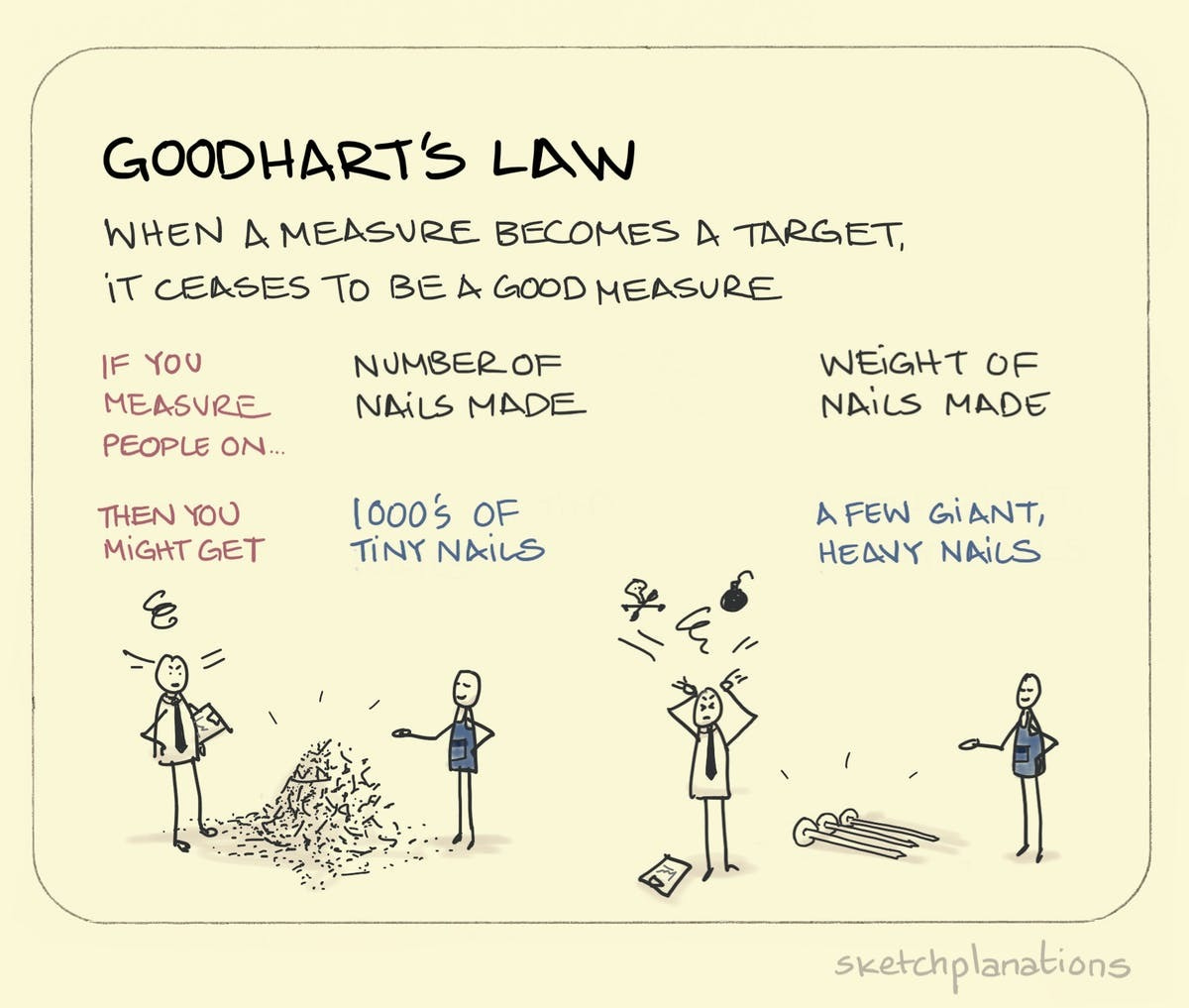

The previous essay explained why optimisation always fails in complex systems as the system inevitably adapts to subvert a single-minded focus on one legible, codified objective. This problem is commonly known as Goodhart’s Law, but it is not restricted to human systems and is common to all complex systems. For example, machine learning/AI suffers from the same problem as most approaches are, by definition, “a process in which a measure is the target”.

The universal response to the inevitable failure of a target metric/measure is to add more metrics. Maybe “using a diverse slate of metrics” can avoid gaming? This is precisely what the Soviet Union tried when it faced the same problem.

A brief history of Soviet economic control

It is common knowledge that planning in the Soviet economy was rife with the problems brought about by Goodhart’s Law and gaming (such as the example in the below graphic). But what this simple story ignores is that the Soviets were well aware of this issue and spent the better part of three decades enacting reforms to solve the problem.

Goodhart’s Law in the Soviet Economy

From the 1930s to the 1960s, Soviet planning optimised to maximise one thing and one thing alone - total output. The managers were incentivised with “stretch” targets and plan fulfilment bonuses. Incentives were more high-powered than in any capitalist economy of the time. For example, achieving a 100% rather than a 99% plan fulfilment could mean an additional bonus of 30%1. This incentive structure was not an accident. Lenin himself argued that communism must be built 'on private interest, on personal incentive, on businesslike accounting'.

Managers also faced a significant stick during the Stalinist era. For example, 40-50% of managers in the coal industry were "fired" in a year. They were fired not just for underperformance but also to prevent cliques from forming between the managers and the ministries, a rampant problem by the 70s (Brezhnev's 'stability of the cadres').

This control structure led to predictable results, with managers manipulating the variables under their control to meet the targets irrespective of whether it made economic sense or not. For example,

cement manufacturers produced only large cement blocks, leading to a shortage of small blocks.

To meet targets set by weight, metal manufacturers focused on heavier materials rather than lightweight, higher quality materials.

Firms overproduced narrow-width cloth in response to targets set in metres.

But even when the Soviet planners fixed these issues, deeper problems persisted.

When the target was expressed in roubles, managers would overproduce more expensive products that required more costly inputs (all prices being a function of the cost of inputs in a planned economy).

Work-in-progress was falsified as final goods to meet targets

Output quality was lowered, especially in consumer goods, where it was less risky (Shoddy producer goods provided to another firm may cause them to complain to the ministry).

The inability to innovate

Even when Soviet firms did not explicitly game the target of output maximisation, they were incentivised to produce what was easier to produce. As a result, firms avoided anything that may hamper plan fulfilment. In Brezhnev’s words, a Soviet enterprise avoided innovation “as the devil shies away from incense”.

The planning bureaucracy and the enterprises they governed were primarily incentivised to meet their plan targets. Any innovation introduces risk and therefore threatens plan fulfilment. Moreover, the innovation that did take place was often a sham. As the Izvestia put it, “the enterprise merely changes a button and the management claims an innovation”.

Reforming the system: more complexity, worse results

By the 1960s, planners well understood these problems and the 1965 reforms were meant to solve the problem of "poorly designed success indicators". They believed that the difficulties of planning could be solved “simply by designing more appropriate indicators for measuring the performance of the enterprise”2. For example, sales revenue and “profit” were installed as new success indicators, and a capital charge was levied on used capital. In addition, the enterprise often had to meet other targets in addition to the output target (e.g. product mix and cost targets).

By the 1980s, enterprises were regulated from above based on several hundred metrics (compared to just a few tens in the early 60s). By 1986,

the enterprises of the Ministry for Electro-Technical Production (Minelektrotekhprom) had to report annually on around 500 indicators, the Ministry of Instrumentation and Control Systems (Minpribor) on 450; the Ministry of Agricultural Machinery (Minselkhozmash) on 600 and the Ministry of the Machine Tool Industry (Minstankoprom) on 400.

Planners also solved problems by establishing new bonus payments to motivate managers. For example, new bonus payments were instituted for innovation, profit, exports, conserving energy etc. The sum of all these changes over time was that managers could not judge what effect any managerial choice would have on their bonus payments anymore.

All this additional complexity made no difference. Even by Gorbachev's time, output targets reigned supreme despite all efforts to displace them and any number of appeals from the planners. Output remained the primary concern of Soviet enterprises and the ministries that controlled them. Why? Because the Plan still had output targets and the ministries above the enterprises had to meet these output targets. At the highest levels, what mattered was still output. The clear evidence was how ministries would often authorise bonuses to firms that met their output targets even if they did not fulfil their other targets.

By the 80s, the Soviet planners had not only failed to solve the problem of inadequate innovation, they were not even maximising output to the extent that they could when planning was “simpler”. Viewed through the lens of the exploration-exploitation tradeoff, control started off trying to maximise exploitation, became more complex to incentivise exploration, and ended up neither exploiting nor exploring due to the gradual subversion of the control system over time.

By the 1980s, the Soviet economy was like a patient whose treatment starts with one medication, only for a succession of new medicines to be added to the treatment to deal with the side effects of prior medications. Eventually, the patient consumes a long list of drugs, yet his life hangs by a thread.

This very same pattern of increasingly complex and ineffective control is being repeated across institutions and systems today. This pattern is the unavoidable progression of codified, "legible" control. Over time, control and optimisation inevitably become more complex, expensive, and less effective.

Most of the information in this essay is derived from Joseph Berliner’s work on the Soviet economy, particularly from his two books, ‘The innovation decision in Soviet industry’ and ‘Soviet Industry: From Stalin to Gorbachev’.

Vladimir Mau in ‘Central Planning in the Soviet System’